For generations, the term bangungot has stirred both fear and fascination among Filipinos. Often described as a terrifying sleep-related phenomenon that claims young and healthy lives, it is commonly linked in folklore to a supernatural being—something mysterious and beyond human control. But modern science is gradually shedding light on this once-elusive “nightmare” and offering medical insights that may help explain and even prevent these untimely deaths. This article explores the cultural roots and superstitions surrounding bangungot, its medical interpretations, and what can be done to bridge traditional beliefs with scientific understanding.

Cultural Origins and Superstitions

The word bangungot loosely translates to “nightmare,” but the traditional concept goes much deeper than a bad dream. In folklore, it’s associated with the batibat—a large, vengeful spirit believed to live in trees. When a tree inhabited by a batibat is used to build a house or furniture, the spirit may follow and sit on the chest of a sleeping person, suffocating them during the night.

To counteract this threat, various protective practices evolved over time. Some Filipinos believe that avoiding a heavy evening meal or sleeping on one’s left side can prevent the batibat from attacking. Others suggest more symbolic acts—like sleeping in women’s clothing, placing garlic under pillows, or reciting prayers—to ward off evil.

These beliefs continue to hold sway, particularly in rural areas, where stories of bangungot are frequently shared and handed down. Some survivors have even described dreams of being pinned down, falling endlessly, or being unable to move—a phenomenon that modern medicine recognizes as sleep paralysis. Yet for many, these eerie sensations are not simply neurological quirks but are proof of the supernatural.

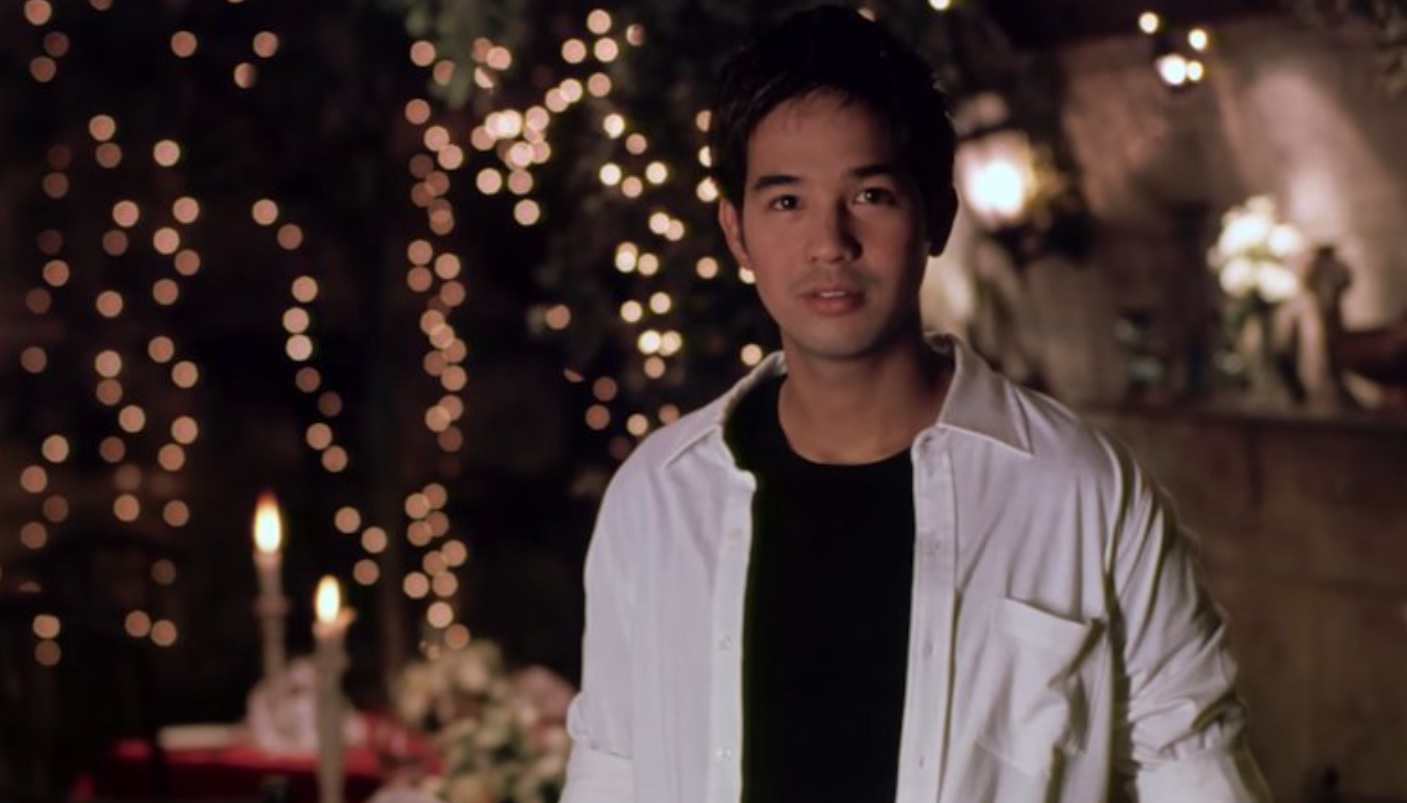

Perhaps one of the most widely remembered cases that reinforced public fear was the death of popular Filipino actor Rico Yan in 2002. At just 27 years old, Yan died in his sleep while on vacation in Puerto Princesa, Palawan. The official cause was cardiac arrest due to acute hemorrhagic pancreatitis, but the public narrative quickly leaned into the idea that he had succumbed to bangungot, forever linking the condition to tragedy in the Filipino consciousness.

Related article: Palawan’s Mystic Beauty

Epidemiology and Prevalence

Though cultural beliefs remain strong, statistical data gives a clearer picture of bangungot as a public health concern. The 2003 Philippine National Nutrition and Health Survey reported an estimated 43 deaths per 100,000 population attributed to bangungot, predominantly affecting young men under 40.

Similar cases have also been documented in other Southeast Asian countries, where the condition is referred to by different names but exhibits the same pattern: sudden, unexplained deaths during sleep among healthy individuals. Known in medical literature as Sudden Unexplained Nocturnal Death Syndrome (SUNDS), this phenomenon has an incidence rate ranging from 26 to 43 per 100,000 in countries like Thailand and Laos.

The demographic consistency is striking—healthy, young males, often after a night of heavy eating or alcohol consumption, found lifeless in their beds by morning. This pattern has fueled further research into underlying physiological causes.

Medical Explanations

One possible medical cause of bangungot is acute hemorrhagic pancreatitis. As explained by Makati Medical Center, this severe inflammation of the pancreas can occur after overindulgence in food or alcohol, particularly before sleep. The condition can progress rapidly, leading to shock, internal bleeding, and death if not immediately treated.

Another explanation gaining ground is Brugada syndrome, a genetic heart condition that affects the electrical activity of the heart. Individuals with Brugada syndrome can appear perfectly healthy but may experience sudden cardiac arrest, often during rest or sleep. A 2012 study published by the U.S. National Library of Medicine noted that many bangungot victims showed no structural damage to the heart upon autopsy, pointing instead to fatal arrhythmias. The condition has been linked to mutations in the SCN5A gene, found in 20–25% of diagnosed Brugada cases. Furthermore, a case study in the International Surgery Journal reported that up to 2% of otherwise healthy Filipinos may show ECG patterns consistent with the syndrome.

While not deadly in itself, sleep paralysis is another phenomenon often confused with bangungot. During sleep paralysis, individuals wake up unable to move and often report pressure on their chest or an ominous presence in the room—experiences that eerily echo folklore accounts. Unlike Brugada or pancreatitis, however, sleep paralysis is typically benign and non-fatal.

Bridging Culture and Medicine

Despite medical advances, many Filipinos continue to lean toward spiritual explanations when facing bangungot-like events. This reliance on folklore can delay critical medical interventions such as heart screenings or consultations for recurring abdominal issues.

In neighboring Thailand, culturally tailored public health campaigns have helped bridge this gap. By involving respected local figures, including monks, Thai health authorities have been able to educate communities about SUNDS as a legitimate medical concern. The Philippines could benefit from similar approaches—ones that honor tradition while encouraging proactive health measures like genetic testing or regular ECGs.

There’s also a strong need for further local research to explore genetic predisposition and environmental risk factors specific to the Filipino population. Better data could guide policies, inform health workers, and ultimately reduce mortality.

Public Health and Prevention Strategies

Preventive measures begin with awareness. Recognizing early warning signs such as fainting, chest pain, nausea, or abdominal discomfort can be life-saving. Families with a history of unexplained sleep deaths are especially encouraged to seek heart screenings or genetic testing.

Lifestyle changes—such as limiting alcohol intake and avoiding rich meals before bed—can also lower risk. Public education campaigns should emphasize that bangungot may have identifiable and treatable medical causes, and that seeking timely care is crucial.

Demystifying the Nightmare

Bangungot continues to straddle the boundary between myth and medicine. While its place in Filipino folklore adds to its mystique, growing evidence shows that it may stem from serious but preventable health conditions. By blending cultural respect with scientific understanding, communities can move toward life-saving awareness and better public health outcomes—proving that even the most fearsome nightmares can be brought into the light.

Check out more of our Health & Wellness article for more interesting topics.

–

Featured Image by hellodoctor